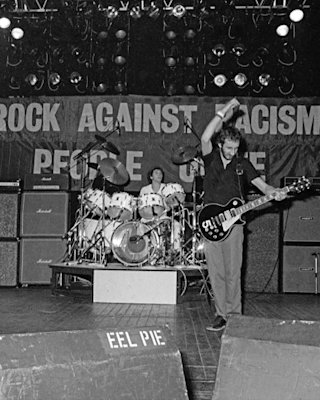

Pete Townshend of The Who utilised Marshall gear to drive the message home at a Rock Against Racism benefit concert in London in 1978.

Off the back of Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in 1968, in which the Conservative MP criticised rates of immigration and opposed the anti-discriminatory Race Relations Bill, Britain was shaken by mounting support for the fascist National Front. As Black footballers were subjected to racist chants, and racially-motivated killings such as that of Sikh teenager Gurdip Singh Chaggar in 1976 took place, British society looked increasingly bleak as immigrants of all nationalities lived in fear of violence.

At the height of this unease, Eric Clapton landed himself in hot water when, at a concert in Birmingham in 1976, he vocalised support for Powell, commanding his audience to “stop Britain from becoming a black colony.” His comments riled the likes of Red Saunders, Jo Wreford and Peter Bruno – who penned a scathing response to NME which was reprinted and circulated en masse. Clapton, after all, was a student of the blues – and had bagged a hit with his cover of Bob Marley’s ‘I Shot The Sheriff’ just a few years prior. He owed a huge debt to the groups he was slandering.

"Who shot the sheriff', Eric? It sure as hell wasn't you!" Red Saunders, Jo Wreford and Peter Bruno, 1976

The trade-off would mark the foundation of one of the UK music industry’s most remarkable anti-racism movements: Rock Against Racism, a politicised cultural organisation that united the country’s hottest musicians against the xenophobia sweeping the nation. “We want rebel music, street music… Music that knows who the real enemy is,” read their manifesto, written by David Widgery in 1976. It ended with a powerful call to arms: “LOVE MUSIC HATE RACISM.”

X-Ray Spex, fronted by British-Somali punk icon Poly Styrene, were one of the first acts on the bill at the Rock Against Racism concert in London’s Victoria Park in 1978., Mick Jones of The Clash, Danny Kustow guitarist in the Tom Robinson Band.

The event was described as the concert that united a nation...

Concerts, club nights and tours would assemble musicians of all ethnicities and backgrounds – with reggae, rock, and punk central to the organisation’s message. On 30 April 1978, Rock Against Racism mounted a historic charge in London: a carnival amassing up to 100,000 anti-fascists marched seven miles from Trafalgar Square to an open-air concert at Victoria Park, in the heart of the National Front stronghold. Headliners included Tom Robinson and The Clash, while Steel Pulse and X-Ray Spex were on the bill elsewhere. The event was described as the concert that united a nation – the culmination of a decade of fervour for punk rock and protest.

Paul Simonon from The Clash playing in front of a crowd at Rock Against Racism’s ‘Carnival Against the Nazis’ concert.

A second carnival mobilised a similar amount of people in September that same year, with the crowd travelling across the Thames from Hyde Park to Brockwell Park to catch performances from Aswad, Elvis Costello and Stiff Little Fingers. Further events underscored the organisation’s perseverance for their cause, and Rock Against Racism’s ambition and influence has spread far and wide in the years since. German anti-fascists held their own concerts under the banner of ‘Rock gegen Rechts’ in Frankfurt in 1979, with latter-day events held in cities like Düsseldorf and Chemnitz in the ‘10s. In 2002, Love Music Hate Racism – named for the slogan found in the original Rock Against Racism manifesto – was founded in Britain, hosting major events in Manchester’s Platt Fields Park the same year, and in London’s Victoria Park to mark 30 years of Rock Against Racism in 2008. They continue to campaign for equality today.